I’m starting this CD reviews series with a personal favorite: My Aim Is True, Elvis Costello’s 1977 full-length—the album where Declan Patrick MacManus conclusively proved that mixing jittery nerd-rock, cynical lit-pop, semi-goofy vintage posturing, and biting, self-aware toxicity makes for a pretty solid angst-pop cocktail.

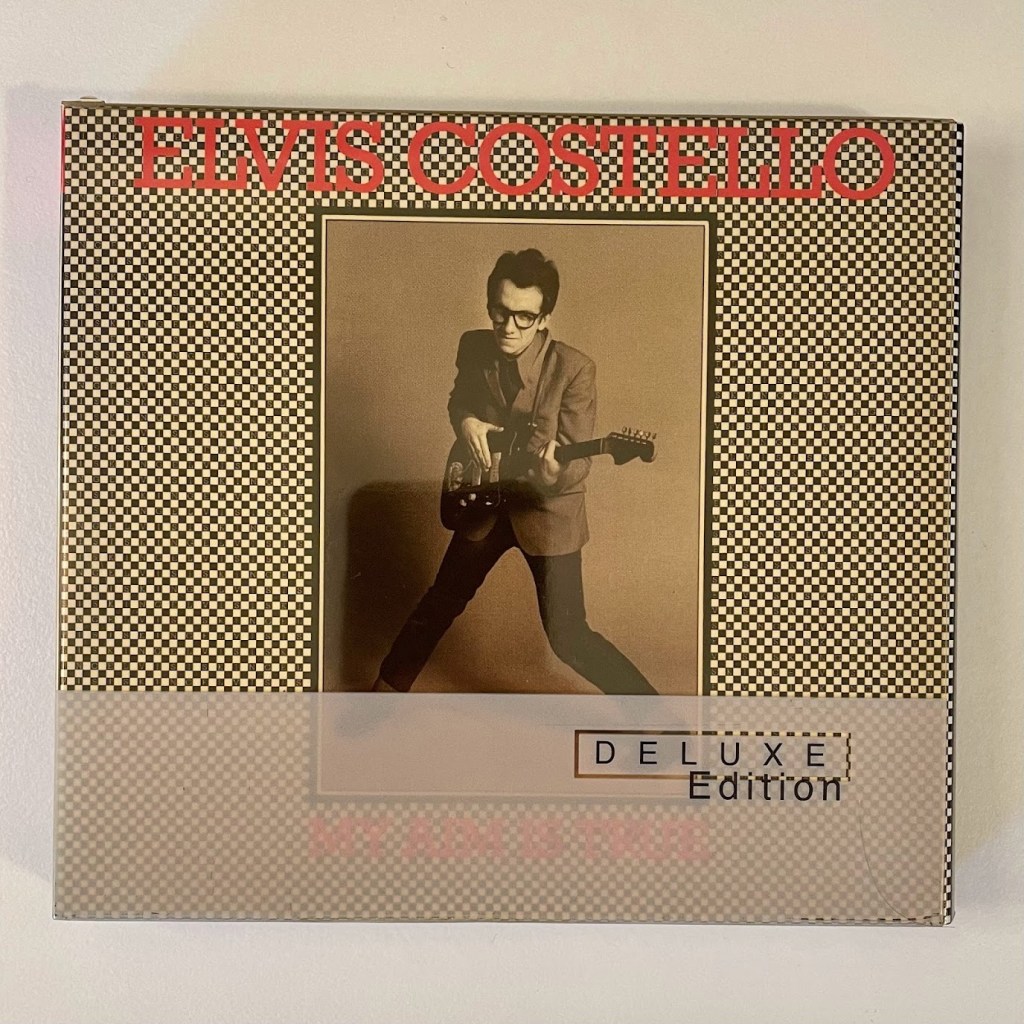

I first heard Costello in high school. It was a chance FM car radio encounter with This Year’s Model banger “Chelsea” on the way to Oakland for a show. I remember being struck by the cryptic menace of the lyrics, the twisted guitar tuning, and the indescribable sense of weirdness that permeated the whole thing. It was almost classic rock, but a whole lot dorkier—and it planted the inkling that Led Zeppelin and all those other 60s hard-blues bands were the posturing, dorky ones all along. Subsequent digging in Dad’s garage turned up an early Greatest Hits collection (because of course it did), and twelve years later, I have two different CD releases of this same album: One I bought at a bookstore in Berkeley, and the other is a two-disc Deluxe Edition that I picked (with permission, I swear) from my girlfriend’s aunt’s collection. And my favorite Costello project is still a dead heat between This Year’s Model and Wise Up Ghost, his arguably fucking superb collaboration with the Roots—but this album, My Aim Is True, is Costello at his scrappiest. It’s completely fundamental to his artistry, and this Deluxe Edition is full of extra demos and live takes that show off his and his band’s substantial chops.

It seems obvious to call this a classic new wave rock album—but could it even be (gasp!) a little punk? Makes sense, considering the scene Costello came up in. So I’m talking punk in the sense that Patti Smith was punk when she did “Gloria,” and so was Television on “See No Evil,” and if you want to stretch it, you had the New York Dolls on “Personality Crisis.” In some ways, Costello’s version of punk was more similar to that of the early proto-punks, and distinct from those of the second generation of punks—the “raging Chuck Berry on heroin” throttle of the Dead Boys, the Voidoids’ arguable art-rock ambitions, and the pure Saturday Morning Cartoons-pummel of the Ramones. Costello filtered it through jaded British hipster fandom: a semi-ironic blend of iconoclasm with hero worship and method acting that still gets him unfairly thrown in with the batch of lesser pub rock and new wave bands of the time—bands around which the man ran laps on laps. There are even ballads here that don’t suck—“Alison” is the biggest hit from this album because it’s equally, gloriously appropriate in a drunk karaoke setting, at a campfire, or at a uniquely fucked-up wedding. And God, God damn, the bitterness! Every song is dripping with it!

I think you can almost trace a certain lineage of incel-esque alternative frontmen from Elvis Costello to Milo Aukerman from Descendents. There are probably a few who come after that. I don’t know, man—Rivers from Weezer? Ok, probably not. But you know the type—awkward-but-literate dirtbag-dorks, a little too smart and a little too rock’n’roll for their own stinkin’ good. Here, Elvis Costello channels a dopesick Holden Caulfield, a shrimpy song-smithing British garage rock-head doing his best take on Morrison, Mick Jagger, and Iggy’s “raw performance-as-poetry” approach. He doesn’t really nail it, but at least he sounds emotionally broken and pissed the fuck off. His sense of melody and fun is impeccable, and the band is just full/good enough that more casual listeners don’t feel ripped off by how short and relatively simple these songs are.

Of course, after a few more albums kinda like this one with the Attractions, Costello got bored of being labeled as an angry young man, and made the switch to more immersive, diverse instrumentation and more reflective, moody songwriting. Not all of that King of America period’s output is great, but it shows the guy’s willingness to confront old artistic habits and throw them out the window when necessary. He’s a restless rock-and-pop auteur who wants to confront his audience by taking them through his ugly characters’ innermost secret thoughts, and he routinely leaves you wondering where autobiography ends and caricature begins.