Why I love Survivor (Destiny’s Child, 2001)

What happens when you take the classic “dramatic musical girl group” concept, isolate its very essence, supersaturate the batter with Chemical X, and turn every knob on the machine up to maximum? Does it spiral hopelessly out of control, or does it manage to produce a musical Powerpuff trio with enough rocket-fueled hip-pop’n’b lift to clear the stratosphere?

I have no idea. I’m just gonna talk about why I love the Destiny’s Child album Survivor.

Flashback: It’s 2001. Destiny’s Child are at the peak of their commercial power. Two albums down, multiple members with true superstar potential, managed by the kind of classic antihero music business-dude you read about in scathing autobiographies decades later—all the ingredients are present. They’re poised to become the singular pop group of the fresh new millennium— maybe they already are. They’re hot off some juicy lineup changes and bitter infighting, like a battle-scarred wildcat standing atop Pride Rock, snarling righteous vengeance into the night.

Yeah, that’s the way the title track sounds to me. It’s a power surge, a goddamn electrical storm. It blows out the entire grid. It shoots lightning confidence out of its fucking fingertips. It’s Halle Berry as Storm in X-Men—coincidentally, a movie released within a year of Survivor. And maybe not so coincidentally—the movie and the album both deal with similar themes of being marginalized, betrayed, condescended, and discarded, and not only surviving, but thriving in spite.

Actually, hang on—let me riff on this for a minute. I want to see if I can make the comparison stick:

Like the mutants in the X-Men universe, Destiny’s Child faced a sonic choice between joining Magneto or Professor X when confronted with the reality of their newfound pop music superpowers, and the dangers of the journey ahead. How to make album three? Should they swallow the same music industry poison that had rocketed them to the international space radio station, but had also ripped their relationships apart? Or, should they—actually, you know what? I take it back. I’m not sure there was ever another option. So maybe it’s not such a great comparison. My bad—should’ve stuck with the Powerpuff Girls.

OK, but they’re still dealing with this concept of resilience. Staying strong in the face of adversity. Wrapped up in that seems to also be the theme of “generally being badass, sexy, strong, and self-assured all at the same time, all the time.” Cool. We get it. Three or four songs in, we still get it. We’re starting to really get it. And then admittedly, the album tends toward “alright, we get it already” from time to time. For example, part of me wonders whether there needs to be an “Independent Women, Part Two.” Not like it’s a bad song, but I don’t know how much it’s adding here. At the very least, maybe we could’ve just saved “Part Two” for a subsequent album—such as any that doesn’t already have “Part One.” With that said, come on—Survivor doesn’t purport to be anything other than a pop classic; thematically, it can’t afford to be subtle. So instead, it sends feminist rallying cries echoing throughout the canyon below the sparkling Destiny’s Child private jet. It screams sexual actualization on “Bootylicious” and “Sexy Daddy,” but it still leaves room for tenderness and vulnerability on “Brown Eyes” and “Dangerously in Love.”

These dance beats are unreal. Slick, sweet, and effortless. So simply easy to listen to, it’s like a deodorant commercial. Think about it—Halle Berry as Storm gets out of an objectively brutal rec center cardio-samba class, miraculously sweat-free—maybe she’s wearing makeup for some inexplicable reason, but it’s a commercial, so we accept it, and as she strides past the rest of the gasping, doubled-over dancers, all eyes in the place are on her. She smells like fresh air. Other songs are almost menacing—”Survivor,” “Nasty Girl,” and “Independent Women” (parts one and two). Unbelievable work overall by producer Rob Fusari, whose other insane credits include “Wild Wild West” by Will Smith, and a shitload of early Lady Gaga songs. The decision to sample Stevie Nicks for “Bootylicious” is inspired on its own—and that’s even without that absolutely profound hook, that viciously self-affirming war cry: “I don’t think you’re ready for this jelly.” More on that song later, by the way—trust me, it’s important.

If you’re the kind of person who reads CD liner notes, this album’s got good ones. Sometimes digging into these inserts gives you a little glimpse of the band members’ personalities, or at least a little insight into what might be brewing beneath the surface. Such is the case here—and after a bevy of shoutouts and thanks, we get to the ladies’ shared pageant-queen acceptance speech: “Finally, thank you to all of you who made it through bad relationships, health issues, discrimination, being abused, death of a loved one, loss of a friend, not being popular, low self-esteem, growing up poor, physical limitations, finances, job loss, pain and suffering, drugs and alcohol, sadness, loneliness…and survived. You are ‘Survivors’.”

And God dammit, that’s corny, but God dammit, that’s a mission statement. That’s what separates a collection of “songs we wrote to put on a record” from a cohesive album. This is a mega-commercial, studio-roided industry hellspawn of a project that sounds amazing and fully executes its present-against-all-odds artistic vision. Yeah, I said it: artistic vision.

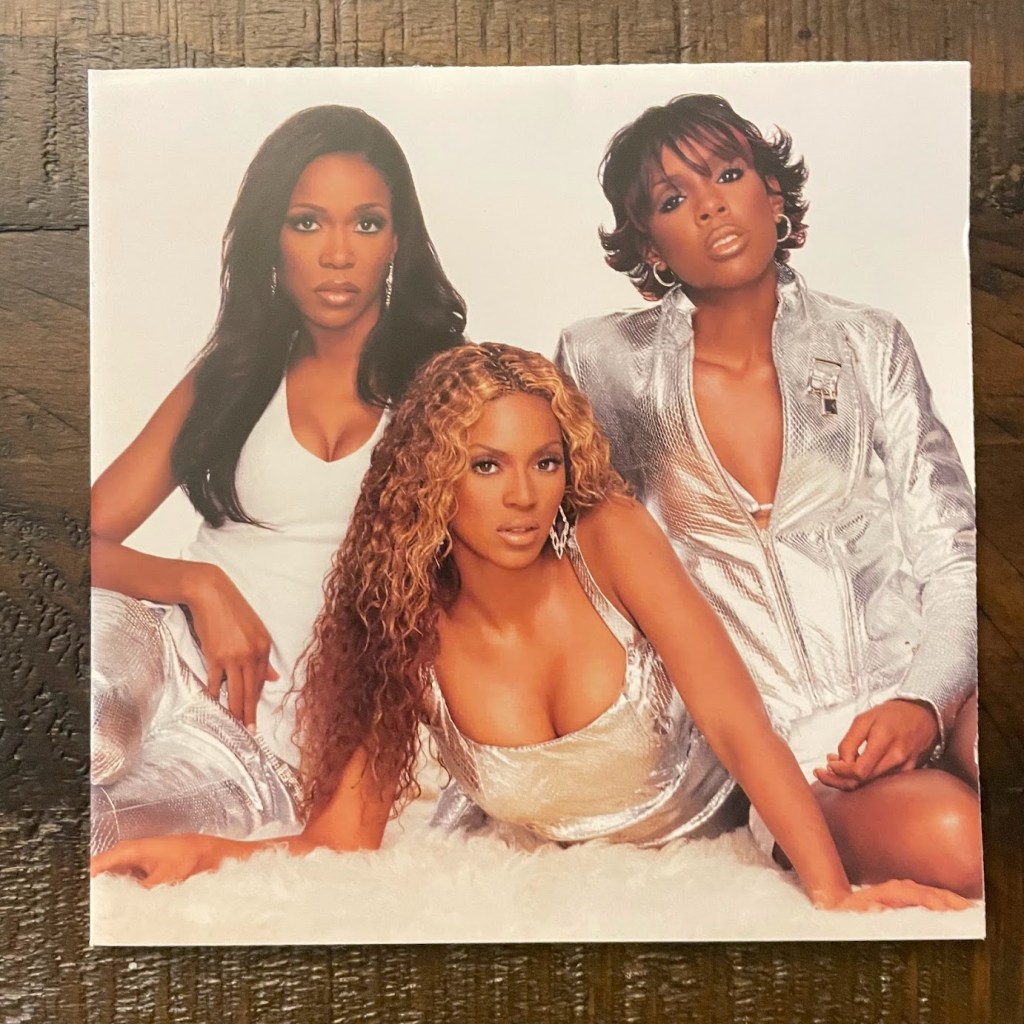

And speaking of artistic vision, let’s have a more complicated conversation about whose vision it was. Obviously, Survivor is more than a spectacular Destiny’s Child album—it’s also a great outing for Beyonce as an individual. We know that—and it’s not just that her singing sounds great—we’re intended to conclude that she tears this album up. She’s laying down on the carpet, dead center of the album cover, bustin’ out of a disco ball-reflective tank top. Kelly and Michelle sit above and (slightly) behind her on either side. Her hair is the lightest and the curliest of the three women. It’s all done with complete transparency, of course. She was the biggest breakout star of the group largely because she was marketed as such. But that’s the thing—she also gets co-producer credits on every single song here. In many ways, it’s her album.

Still, it’s arguably easier to get producer credits when you share a last name with the album’s Executive Producer. And Rob Fusari (the guy I mentioned who went on to work with Lady Gaga) disputes some of Beyonce’s stories of creative inspiration—the decision to sample Stevie for “Bootylicious” was a brilliant one, but whose decision was it? Rob’s, or Bey’s? And how much of the Beyonce mythology needs to be strictly factually accurate? To what extent do we, the audience, need it to be?

Beyonce’s “thank-you’s” at the end of the CD insert liner notes don’t exactly clear up the narrative. After a few thank-you’s to God, her guardian angels, and a healthy “Hallelujah,” the future queen moves quickly to “[m]y parents, the backbone behind Destiny’s Child.” The salute to her mama is benignly genuine, but then we get to Daddy Lessons. “Daddy, you are the strongest man I know. The best daddy in the world. The older I get, the more I realize that you are so kind and generous and a marketing genius (ha! ha!). There would be no Destiny’s Child without you. I love you.” Oh, and don’t forget her message to Solange: “I can’t wait for you to bless the world.” In other words, stay tuned, consumers.

I say all of that, and then offer the following cowardly, equivocating, shitheaded disclaimer: I still heavily bow my head to the bulk of Beyonce’s music. At the very least, I enjoy pretty much every album Beyonce has ever recorded. I feel like Lemonade kinda went over my head or something, but the self-titled album changed the way I think about pop music, and maybe divas generally too. And in spite of that, relatively speaking, I am not a Beyonce diehard by any means. Not even for any specific reason. It does say something about the diehards she has, though.

Look—I don’t need to get into the validity of the cult of Beyonce right now—or ever. I’m not gonna talk about whether she’s deserving of all the heroine worship from a horde of drooling fanatics. I’m not going to begin to address the question of “she’s good, but how good is she actually? Is she historic?” I’m never going to talk about that. Because I value my own life too much. You have to admit though—there’s something weirdly contradictory about the bright-and-shiny message of Survivor and the fact that Survivor started with a nepotism-denying dis track about departing bandmates.

But that’s all part of why I love the album. I love that we have these shared pop media myths, these accusations, betrayals, comebacks, and comeuppances, scattered throughout our collective media existence—these unseemly historical corners of superstardom where idealized artistry and demonized industry collided, and each one sort of became the other. Destiny’s Child—or Matthew “Professor Utonium” Knowles, or Beyonce, or someone (maybe even Rob Fusari) made art out of the toxic industry on Survivor. Not only that—they built a shimmering masterpiece, a monolithic pop music Tower of Babel, an idolatrous tribute to, and reflection of the music industry itself—out of that very music industry’s own ugliest bones and fossil-fuel secretions. That crown? Who really knows if she bought it? Who cares? And that throne? They didn’t buy it—they built it. We all bought it.

(by the way—Beyonce is Blossom, Michelle is Bubbles, and Kelly is Buttercup)